The Covid-19 pandemic has worsened the quality of democracy in a number of Asia Pacific countries. This condition especially occurs in countries that have shown symptoms of a decline in the quality of democracy before the pandemic, such as the Philippines and Malaysia. This happens, according to the Program Director of the Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA) for the Asia Pacific Region, Leena Rikkila Tamang, is the result of a decline in basic rights, government oversight, independent courts, media integrity, parliamentary effectiveness, and a rising of the corruption index.

“The decline can be seen by the deepening inequalities of democracy and the strengthening of the authoritarian regime,” said Leena in a webinar entitled Democracy in Pandemic: Perspectives from Asia-Pacific organized by the Association for Elections and Democracy (Perludem) on Friday, August 6, 2021.

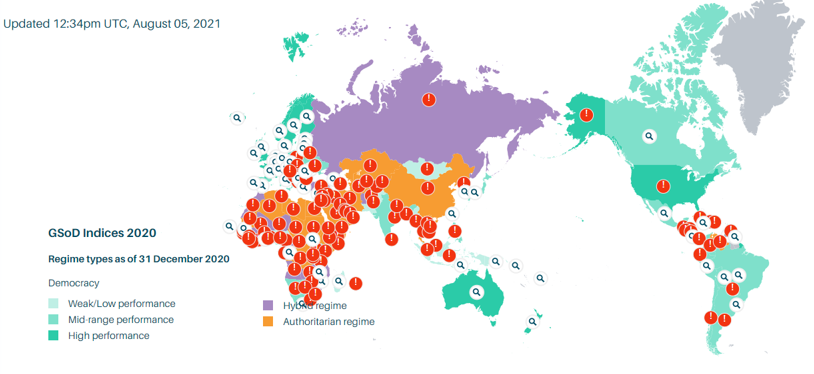

In this case, IDEA divides the quality of democracy in the Asia Pacific region into three categories, namely the state of democratic high, medium, and weak democracies. Based on the 2020 Global Democracy Index, the number of medium-sized democracies dropped to 45 percent. Within this group, the countries that experienced the most significant decline in quality were Indonesia, the Philippines, and Sri Lanka. While countries with a weak democratic quality of the percentage rising to 45 percent with the inclusion of Malaysia, Myanmar, and Papua New Guinea. The percentage of countries with a weak democratic quality is higher than in countries with a high democratic quality, which is only around 10 percent.

According to Leena, the decline in the quality of Indonesia’s democracy occurred only in a short time in 2020. In fact, from 2015 to 2019 the position of Indonesia was still at the middle level. But since last year, the quality of democracy in Indonesia has slumped as political participation and representation of governance, dealing with corruption, social rights and freedom of religion suffered a setback.

The Associate Professor of the Australian National University (ANU), Marcus Mietzner assessed that the Indonesian government tends to take advantage of the pandemic to avoid democratic procedures in the making of policies, such as public participation. This is can be seen from the government’s efforts to encourage the issuance of Law 11 of 2020 concerning Job Creation Law or known as the Omnibus Law amidst the public restrictions on gathering and demonstrating. Though the bill gets a lot of rejections from labor, civil society, environmental activists, and students. “What the government is doing, is forcing a problematic rule with the problematic democratic procedures. There is no dialogue, there is only public rhetoric using the power of the pandemic to achieve government interests,” he said.

In addition, Marcus also highlighted the legal proceedings against Rizieq Shihab. The ex-supreme leader of the Islamic Defenders Front (FPI) was previously sentenced to 4 years in prison for spreading false news about the results of the swab test at the Bogor-based Ummi Hospital. Rizieq was also once considered to have violated the Covid-19 medical protocol. Even though at the same time, according to him, a number of officials have also violated the same medical protocol but did not receive any sanctions. “The reality is that although Habib is not democratic, it is clear that the government is using the pandemic to get rid of political opponents,” he said.

All countries, according to Markus, are experiencing suffering pressure due to the pandemic. However, a number of countries in Southeast Asia appear to have experienced a worse effect than other countries. He said this is the impact of the weakness of democratic institutions, whether executive, legislative and judicial.

In Indonesia, the Secretary-General of the Alliance of Independent Journalists (AJI), Ika Ningtyas, stated that not a few journalists have experienced terror, physical violence, and cyber attacks, such as doxing and hacking. From March to June 2021, there were 16 cases of violence against journalists in Indonesia. Among other things, happened to Tempo journalist, Nurhadi when trying to ask for clarification from a former official of the Directorate General of Taxes Angin Prayitno Aji at the Samudra Bumimoro Building, Krembangan, Surabaya on Saturday, March 27, 2021. At that time Nurhadi was beaten, strangled and his work equipment was damaged by a number of members of the police and organizer event. The East Java Police have named two non-commissioned officers as suspects. While the case file is still being processed at the East Java High Court.

On past August 21, Tempo.co and Tirto.id were also hacked. Even though unsuccessful, the perpetrators of hacking against Tempo.co tried to shut down the server and change the appearance of the Tempo.co website. While, Tirto.id’s intrusion occurred through hacking of the editor’s email account. The hackers then managed to break into the content management system and deleted 7 articles.

According to Ika, the press is also facing the labeling of hoax news. On the news about 63 patients who died in Yogyakarta-based hospitals DR Sardjito due to running out of oxygen cylinders, for example, they received a hoax label from the Indonesian Police. Meanwhile, in various areas such as Purbalingga and Jombang, propaganda has also emerged so as not to disseminate the news about Covid because it is considered will reduce the immune of the community. “This jeopardizes freedom of expression. This propaganda is dangerous because it prevents the public from getting the right information to make decisions,” she explained.

In the midst of the blow to democratic instruments such as the press, the Covid-19 pandemic has also hit the mass media business. The AJI survey results in 2020 showed that there were layoffs, delays, and salary cuts. Of the 700 respondents, a journalist who experienced salary delays ranged from 24.7 percent, cuts as much as 53.9 percent, and workers who were fired reached 5.9 percent.

The conditions in Indonesia are not much different from several countries in the Asia Pacific. The pandemic has strengthened the power of authority over society, so the government often uses an autocratic approach. However, some countries are also considered successful in implementing democratic values in the handling of the pandemic. Such as Germany, Norway, Finland, Taiwan, and South Korea. Where these countries are deemed to have been attentive to the needs of society and discuss with scientists and the communities in the decision-making process.

Member of the National Union of Journalists of the Philippines, Jonathan De Santos told how the condition of press freedom in his country during the Covid-19 pandemic. According to him, the administration of President Rodrigo Duterte employs hundreds of social media specialists to disseminate government propaganda. At the same time, a number of social media accounts were removed for being identified as inauthentic behavior or violating the provisions. In addition, he said, the Ministry of Technology and Military is also suspected of carrying out digital attacks against alternative media. “When it was delivered to the government, they denied it but did not conduct an in-depth investigation,” he said.

During the pandemic, the Philippine government also issued the Bayanihan Act which gave Duterte additional authority to deal with the Covid-19 pandemic and economic stimulus. One of the articles in this act contains sanctions for spreading false news. According to Jonathan, this regulation is problematic because it is was used to attack journalists who criticize the government. During the pandemic, it has been three journalists were facing lawsuits dissemination of false news while covering the handling of the pandemic and the distribution of aid. Thus, the number of cases against journalists in the Philippines from 2016 to 2021 is as many as 223 cases. “Since the pandemic, this amount of intimidation has increased significantly,” he said.

Meanwhile, in Cambodia, a member of the Alliance of Cambodian Journalists, Nop Vy, said the Ministry of Information and Police had banned journalists from reporting on cases that were still in legal proceedings. Journalists who violate these orders could be taken to court and threatened with prison. This restriction, according to Nop, worsens media freedom in Cambodia, which has been problematic for a long time. “The political turmoil that has taken place since four years ago has shut down many independent media outlets, experienced physical violence and lawsuits against many journalists,” he said.

According to Nop, journalists in Cambodia could end up in prison for 6 months just for citing the prime minister’s statement regarding the fate of online taxi drivers during the Covid-19 pandemic. There are also journalists who were arrested and deported for criticizing the purchase of vaccines produced in China.

Even though the Asia Pacific region has experienced a decline in the quality of democracy, the Director of the Asian Network for Free and Fair Elections, Chandanie Watawala, mentions that some Asian Pacific countries were quite successful in holding general elections. Of the 16 countries scheduled to hold elections since January 2020 up to now, only three countries were still postponing, namely Hong Kong, India, and Pakistan. He hoped that the government in each country which will hold the election is committed to increasing the budget of risk mitigation, revising the rules in order to increase voter participation, and implementing a medical procedure.

Until the upcoming June 2022, there will be 7 elections in Asia, including the Hong Kong legislative election (December 2021), the Taiwan referendum (December 2021), the Japanese election (not scheduled yet), the Nepal election (November-December 2021), the Philippine presidential election (November 2021). 9 May 2022), the election of the President of Timor Leste (24 March 2022), and the Cambodian election (June 2022). (Debora Blandina Sinambela)