Two years after Rodrigo Duterte’s 2016 presidential election, Facebook’s Director of Policy for Elections Katie Harbath just ranked the Philippines as the first victim of using social media to win elections. A month later, a similar method was apparently used in Europe which led the United Kingdom to win a referendum from the European Union, also known as Brexit. Meanwhile, similar propaganda widely circulated on social media that was launched during the election in the United States succeeded in leading Donald Trump to become president.

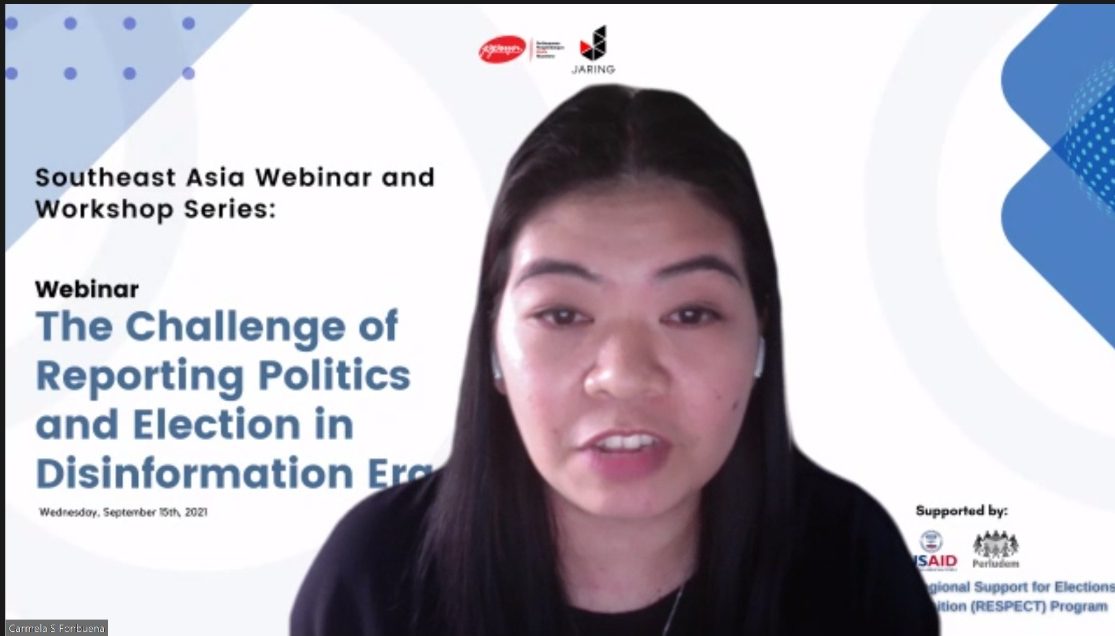

The three of these elections are characterized by massive disinformation by supporters and candidate teams,” ” Executive Director of the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism (PCIJ) Carmella S. Fonbuenakata at the Regional Seminar on Challenges of Media Covering Politics and Elections Amidst Disinformation on September 15, 2021.

a data released by Facebook for 7 months prior to the vote, about 17.9 million people were involved in discussing the Philippine presidential election. More than 176 million interactions such as likes, shares, and comments on social media. According to Carmella, the number is very large considering the number of voters in the Philippines is only around 50 million people.

Several forms of disinformation circulating in the 2016 Philippine election, including claims of support that Duterte received from world figures such as the Pope, celebrities, and even Queen Elizabeth. There have been claims that Duterte was a source of inspiration for former Singaporean Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew. “This is how people are trying to be misled. We realized that the information was problematic, but at the time we did not understand the long-term impact of this problem,” he said.

Long after the 2016 Philippine elections were over, Facebook shut down 200 accounts linked to Duterte’s social media strategy. These accounts are indicated to be inauthentic activity. However, Carmella regretted that the spread of misleading information could not be prevented in the 2019 mid-term elections. At that time, the same method was used by all parties to win the legislative elections.

According to Carmella, social media is used so that the public does not trust the information distributed by mainstream media in the Philippines. Recently, the Inquirer, one of the print media in the Philippines, brought up the corruption in handling the pandemic by the Duterte group. This coverage is a continuation of the findings of an independent auditor body against the Duterte administration. However, what is circulating on social media is that the corruption report is claimed to be an attempt to defame Duterte. “There are so many issues and agendas that are trying to attract public attention and it becomes a challenge for the media to fulfill their responsibility to provide information to voters,” he said.

Learning from this experience, PCIJ as a media that focuses on investigative coverage is trying to countering disinformation by investigating candidate campaign funds. By opening campaign funds, he is sure that the public will know the source and how the money is used.

PCIJ just started a program to monitor social media and also advertisements to calculate candidate campaign spending on social media since May 2021 or a year before the 2022 elections. Next year, the Philippines will hold presidential and vice-presidential elections. President Duterte plans to run for the office again but he can be no longer run for the number 1 position. Because the law in the Philippines does not allow a president to serve two terms after 6 years in power.

According to Carmella, data on the sum of money which the candidates spend on political campaigns on Facebook can be easily exploited by journalists. But unfortunately, the openness that Facebook has done still has not been applied to other social media, such as Youtube. “Another challenge is that the candidates also use influencers who mislead the public. We are still looking for ways how to uncover the flow of campaign funds for influencers,” he said.

Apart from investigations source, collaborations between the media and the non-governmental organizations were also formed to tackle disinformation. The fact-checking movement has been started to emerge in 2019 and is already working for the 2022 Philippine elections. The fact-checking movement is carried out by examining the claims of figures, candidates, and false news circulating on social media.

The fact check movement is widely used in various countries, including Indonesia. The Executive Editor of Tempo —one of the mass media outlets in Indonesia, Yandhrie Arvian, said that his media had created a special channel to fight false news since 2016. Initially, the information that was examined just only related to the latest news and information, not all of the fake news circulating on social media. Later they checked the broader facts. “Initially we were not aware of the extent of this phenomenon and very few resources were available to reach it,” Yandhrie said.

Yandhrie said fact-checking was carried out more massively during the election because the spread of fake news was increasingly high and dangerous. For example, in the 2014 Indonesia presidential election, fake news and calls for violence were very high on social media. This was triggered by political polarization, so that fake news was used to mobilize voters and legitimize political power. The two candidates who contested in the 2014 Presidential Election produced false news and inaccurate information.

At that time, media content was also used by the candidate supporters to manipulate facts. According to Yandrie, there are not a few old news that is deliberately resurfaced to construct public perception and serve as a context for many issues. News headlines were even intentionally changed and distributed to be used to attack political opponents. This situation, he said, made the public’s trust in the media diminish.

Unfortunately, Yandhrie said that several television media were also affiliated with the candidate to construct their version of the facts. There are also media outlets that unknowingly spread false news because they quoted candidates and their supporters without verifying the facts presented. “During the election period, our fact-checking team produced a daily fact check,” he said.

Tempo examines candidate claims by examining sources who submitted information or claims, facts after the examination, as well as the reference or basis for Tempo making an assessment. Tempo even went so far as to examine every fact that was presented during the candidate debates that were broadcast live on television and radio. They check each claim and publish the results of those checks on Facebook and Twitter. This was done by Tempo during the 2017 DKI Jakarta gubernatorial election and the 2019 Presidential Election.

From every fact-checking carried out by the media, Yandhrie said that the media should not be partisan and must be open to any sources used to check facts, be open to sources of funding, be open to fact-checking methods, and be ready to responsibly correct any mistakes if something goes wrong.

In this case, Tempo is not alone. In the 2019 election, Tempo collaborated with a number of online media and hoax-busters organizations such as Google News Initiative, Mafindo, and First Draft News. Collaboration provides a number of advantages, such as increasing the credibility and competence of the media, so that the public has more trust. “Fact-checking is most crucial during the elections so people can vote with confidence and know the profile and background of each candidate,” he said.

Unfortunately, not all media can easily prevent the misinformation produced by politicians and the government. Thai journalist Hathairat Phaholtap said that since 2014 the media in Thailand has been under military surveillance. There are at least three regulations that restrict the media from criticizing the military. Among other things, Law 112. This regulation, according to him, threatens the freedom of the press because anyone who defames and insults the king, queen, heir, and regent will be sentenced to 3-15 years in prison. “During the 2019 election, the media could not even cover the election process,” he said.

The Thai Council for Peace and Order (NCPO) has banned international organizations from monitoring elections. They also manipulate the vote count, so that they can gain majority support. Meanwhile, during the Covid-19 pandemic, the government uses the Emergency Act to silence the press. Even the media that are against this rule are reported to the courts. “Facing this challenge, I don’t know what to say. I just told the staff to be a good journalist, be brave. We hope that the media associations in Thailand will give their support to the media,” he said.

Meanwhile, Eni Mulia, Executive Director of The Indonesian Association for Media Development (PPMN), one of the civil organizations in Indonesia, said that the Covid-19 pandemic has worsened the condition of the media which has been disrupted by various problems, ranging from economic pressures and digital developments.

The Press Freedom Index, released by Reporters Without Borders in April 2021, shows a poor portrait of press freedom in three-quarters of the 180 countries. In Southeast Asia, Vietnam was ranked the lowest in terms of press freedom, while Timor Leste was top with a press freedom index score of 29.11 points. Indonesia and Malaysia followed with index scores of 37.4 and 39.47 respectively. Thailand and the Philippines are under Malaysia with scores of 45.22 and 45.64.

However, the presence of the media is increasingly needed to produce good quality information. The practice of good quality journalism will save the lives of many people and keep democracy alive. “We can’t just sit still watching this phenomenon. We have to produce good quality information and journalism in the era of disinformation,” said Eni.

Eni said that this activity was an effort to support the media in producing political and election issues amidst disinformation.

The series of activities will be held with webinars and training with a number of journalists in Southeast Asia. This activity took place thanks to the support of the Association for Elections and Democracy (Perludem) under the program of The Asia-Pacific Regional Support for Elections and Political Transition.