Child marriage is a violation of Marriage Law no. 1/1971 and contravenes Law no. 23/2002 on Child Protection, violating children’s rights and creating problems for the children born to those marriages.

The alarm needs to be raised about the emergency of the practice of child marriages. The high incidence of underage marriages places South Sulawesi in fourth position in Indonesia after West Sulawesi, Kalimantan, and Nusa Tenggara Barat (NTB). In 2017, based on data (Simphoni) from the Women’s Empowerment and Child Protection Agency (DP3A) of South Sulawesi, 333 child marriages took place, increasing the following year to 700 cases.

Although Makassar experiences the lowest rate of child marriages (8 percent) in 24 regencies/cities in South Sulawesi, the Head of Bidang Statistik Sosial Badan Pusat Statistik (Central Statistics Agency; BPS) South Sulawesi, Fahruddin, said that the figure is relatively high. Of girls aged less than 16 years, 5.01 percent are already married, while the figure for boys is relatively low at 0.52 percent. For girls between the ages of 16 and 18, 17.13 percent are already married, while for boys the figure is 3.73 percent.

Child marriage cases in Makassar occur in almost all remote subdistricts. These cases prevail in the west of Makassar, a coastal area which is now an island subdistrict. In Sangkarrang subdistrict, an expansion area designated by Local Regulation on Subdistrict Expansion Numbers 2 and 3 in 2015, underage marriage is very common.

The incidence of children marrying before graduating from secondary high school is common, especially in Kodingareng village, the largest island in the subdistrict. With an area of approximately one square kilometre, and accessed from the mainland of Makassar city in 40 minutes, it is a densely populated island (4,000 persons with 3,000 family heads).

Houses in Kodingareng are built side-by-side, and the dense population in the limited area has caused many residents to leave the island in search of better livelihoods. This condition, in which many children are left on the island to fend for themselves and living separately from their parents, has triggered child marriages. There are only two boats to transport passengers to the island, and a limit to the number of passengers who can be transported at one time (about 50). Members of the island communities working in the city sometimes return only at weekends to meet their families, which is why parents in this situation prefer to marry off their girls so that they are not burdened with raising them. Moreover, if children begin dating, they must be married quickly.

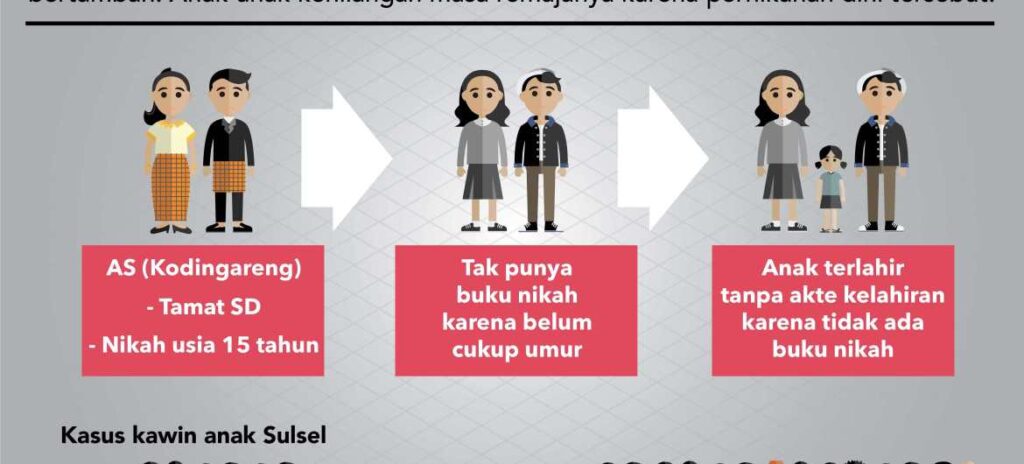

AS (17), was married early in Kodingareng; she was only 15 years old when she received a marriage proposal. Born in 2001, AS had received education only to the level of elementary school. After graduating, and with no funds with which to pay the tuition fee, AS did not continue her studies. Moreover, her parents did not live on the island. “After graduating from primary school, I immediately followed my parents to Taeng in Gowa regency, and I could not continue my study,” AS said. Not more than two years after getting married, AS had to return to her parents. She was mourning the death of her husband with whom she had had a daughter.

Her husband passed away when his daughter was only three months old. He had suffered from a high fever for days, ultimately causing his death. Now AS is left with the responsibility of raising her child alone. “I do any work I can to enable me to raise my child; in the morning, I join my parents-in-law to sell cookies around the village. Alhamdulillah [thank God] I can buy snacks for my child.” The saddest and most regrettable thing is that to this day, AS’s child is not registered with the Office of Population and Civil Registration as a community member of Makassar.

Absence of a marriage book when her child was born in mid-2017 has caused AS to be unable to obtain a birth certificate. “I tried once to apply for it, but was asked to show the marriage book, which I don’t have. Pak Imam said, later when you are 17 years old, I will give it to you,” AS told.

In Kodingareng, there are more than a few people marrying without marriage books. On the island the majority of residents are fishermen, and a marriage book is not an important thing. For those who marry young, an alternative to falsifying the documents for state recognition is just to marry whether the state wishes to acknowledge it or not.

The early marriage story of AS is similar to that for other marriages not complying with the requirements of marriage documents, as defined in Islamic Law Compilation (KHI) Presidential Instruction no. 1/1991 Article 6 paragraphs (1) and (2) and Articles 4, 5 and 7 on Marriage Registration. Article 4 on Islamic Law Compilation confirms that legal marriage is a marriage which complies with Islamic Law in accordance with Article 2 paragraph (1) Law no. 1/1974 on Marriage. It states that a marriage is legal, and is solemnised according to the law of each religion and belief. Meanwhile Article 5 of the Islamic Law Compilation states that Muslim marriages shall be registered and solemnised in accordance with Law no. 22/1946 and Law no. 32/1954. Article 6 confirms that the marriage shall be solemnised before a Marriage Registrar (PPN), failing which the marriage has no legal effect. Article 7 confirms that the marriage shall be evidenced by a marriage certificate; if not, the marriage can be verified.

The form of a child marriage can be privately made to comply with the requirements of religious law, and even with incorrect (illegal) facts can be legally registered at the Office of Religious Affairs without a petition for dispensation to the Religious Court. Forging documents or marking up a child’s age is one of the cases found on Kodingareng island.

One of the parents in Kodingareng, Intan (not her real name) admitted that every day girls not yet 16 years old and still in the first grade of senior high school are married. An unexpected marriage took place in 2012. Intan admitted that she actually wished that her child would not marry so soon; moreover her eldest daughter was still studying. However, she could not refuse the wish expressed by her mother to see her grandchild wearing a bridal costume. “My mother, her grandmother, was sickly. She wanted to see her grandchild married before she died,” Intan said. The man proposing to her daughter is a close family member, making it difficult for her to refuse.

Even though the child was below legal marriageable age, the local Office of Religious Affairs registered the marriage, which was marked by the evidence of a marriage book as a legal form of marriage. Intan admitted that the local Imam was forced to add six years to the girl’s original age to legalise the marriage.

Referring to her daughter’s birth certificate issued by the Civil Registration Office, her child was born on 3 August 1996, while the year of birth in the marriage book and course certificate of the bride/groom (Suscatim) issued by the Agency for Development and Preservation of Marriage (BP4) of the subdistrict was stated to be 1990. “I didn’t really know how Pak Imam marked up the age, what I know now from reading the marriage book is that it can be done,” Intan said last February.

Intan did not exactly know how the Imam satisfied the document administration process required for the marriage of her child. She also admitted that she did not spend even a cent for the registration of her daughter’s marriage at the Office of Religious Affairs, or for issuance of the marriage book. What was done by the local Imam, Intan said, was help the relatives without any bribe. “I didn’t exactly know how the (marriage book) was issued,” she said.

In accordance with Chapter IX on Perjury and False statement, Article 242 paragraph (1) Criminal Code, explains that whoever knowingly makes a false statement under oath, whether verbally or in writing, personally or by his/her attorney, is liable for imprisonment of up to a maximum of seven years.

Always Wrong

The Imam in Kodingareng village, Rahman, said that he was often facing a dillema when being asked to solemnise an underage marriage. Rahman understands that child marriage is not permitted by law, but said he would be bullied by local residents if refusing to marry off a child failing to comply with the regulations. “In the wrong no matter what, we wanted to solemnise the marriage, but the bride was underage. If the marriage is cancelled, we will be the enemy of the people in the village,” Rahman explained.

Rahman admitted that the marriage of children solemnised by him without petition for dispensation in the Religious Court received state legality. It was done by marking up the age of the prospective bride/groom. However, around 2016, this practice could no longer be carried out because the rules and system no longer permitted it. Lately, many underage married couples do not have a marriage book, due to stricter regulations and supervision.

“Previously, submitting a family registration card (KK) and forms N1,N2 and N4 was enough, we could easily mark up the age as it would not be verified,” said Rahman, the Imam in Kodingareng since 2008. Besides the requirements for civil information such as RIC, academic certificate, family registration card and birth certificate, marriage registration is now online, and the process of age verification cannot be manipulated.

Rahman can promise a marriage book to a young married couple only if their ages comply with Article 7 paragraph (1) of the Marriage Law. The law states that the lowest age for a legal marriage for girls is 16 years old and for boys, 19 years old.

Meanwhile, Article 7 paragraph (2) of the Law permits girls and boys who marry early to submit a dispensation request to the Religious Court. When Rahman was an Imam, no child marriage in Kodingareng held a letter of dispensation from the Religious Court. “I have no idea about what a dispensation is. The point is, when there was a submission for marriage of underage children, I just refused them and asked them to wait until they attained the permitted age, at which time I would start to process the marriage book,” Rahman explained.

Rahman admitted that he is well informed about the law. If there was a guardian or parents wishing to register their family members who were still underage, he immediately refused their request and did not process them at the Office of Religious Affairs. However, the marriage was not automatically annulled. The parents of the child married off their child without the Imam. “Those marrying off the children are their parents, I did not want to take any risk,” he said. His presence as an Imam was no longer respected by the local community, and if it was not members of his own family wishing to marry, Rahman was not informed.

“Sometimes a few days before a child got married, the parents came to inform me. Sometimes, I was not informed if it was not members of my own family who would marry. I was invited to the wedding not because I am an Imam, but a relative,” said Rahman, explaining the reason why many couples, especially married children, have no marriage book.

No More Age Manipulation

Based on the marriage book with the Office of Religious Affairs in Ujung Tanah subdistrict, recommendation for petition of dispensation was never issued in 2018. There was only a petition for a cover note to the Religious Court which was never followed up on by the petitioner. “In this case, sometimes the child was married, but unregistered,” said the Head of Office of Religious Affairs Ujung Tanah, Afdal, at his office.

Afdal, who became Head of the Office of Religious Affairs in Ujung Tanah in May 2017, explained that with the issuance of the Minister of Religion Regulation no. 19/2018 on Marriage Registration, age manipulation became impossible. He said that the regulation set forth the new requirements for completeness of documents from the prospective bride and groom. While in previous years, marriage would only need the RIC or family registration card as substitute to the RIC, now the birth certificate and academic certificate of the prospective bride and groom should be enclosed.

Legal protection, Afdal said, is also one of the efforts to suppress the child marriage rate. It includes a web-based Marriage Management Information System (Simkah), online registration for which is difficult for prospective underage brides and grooms to access. This web-based system, Afdal continued, is connected with population data at the Office of Population and Civil Registration (Dukcapil). “So, when the officer inputs the national identity number (NIK), the age will be read, and age data manipulation is impossible, because the system goes into error immediately and prevents the marriage book from being issued,” Afdal explained.